By Sergey Tselovalnikov on 09 December 2025

Join the on-call roster, it’ll change your life

Imagine you are a software engineer a few years into your career, working on a service that is an important part of a large production system. One day in a routine 1:1, your manager mentions that there is a gap in the on-call roster and asks if you would like to join the rotation. The concept is simple, if the error rate spikes while it is your turn in the rotation, you'll get an alert. When that happens at any time of day, you'll need to open your laptop, investigate and restore the system. They even mention there is extra pay.

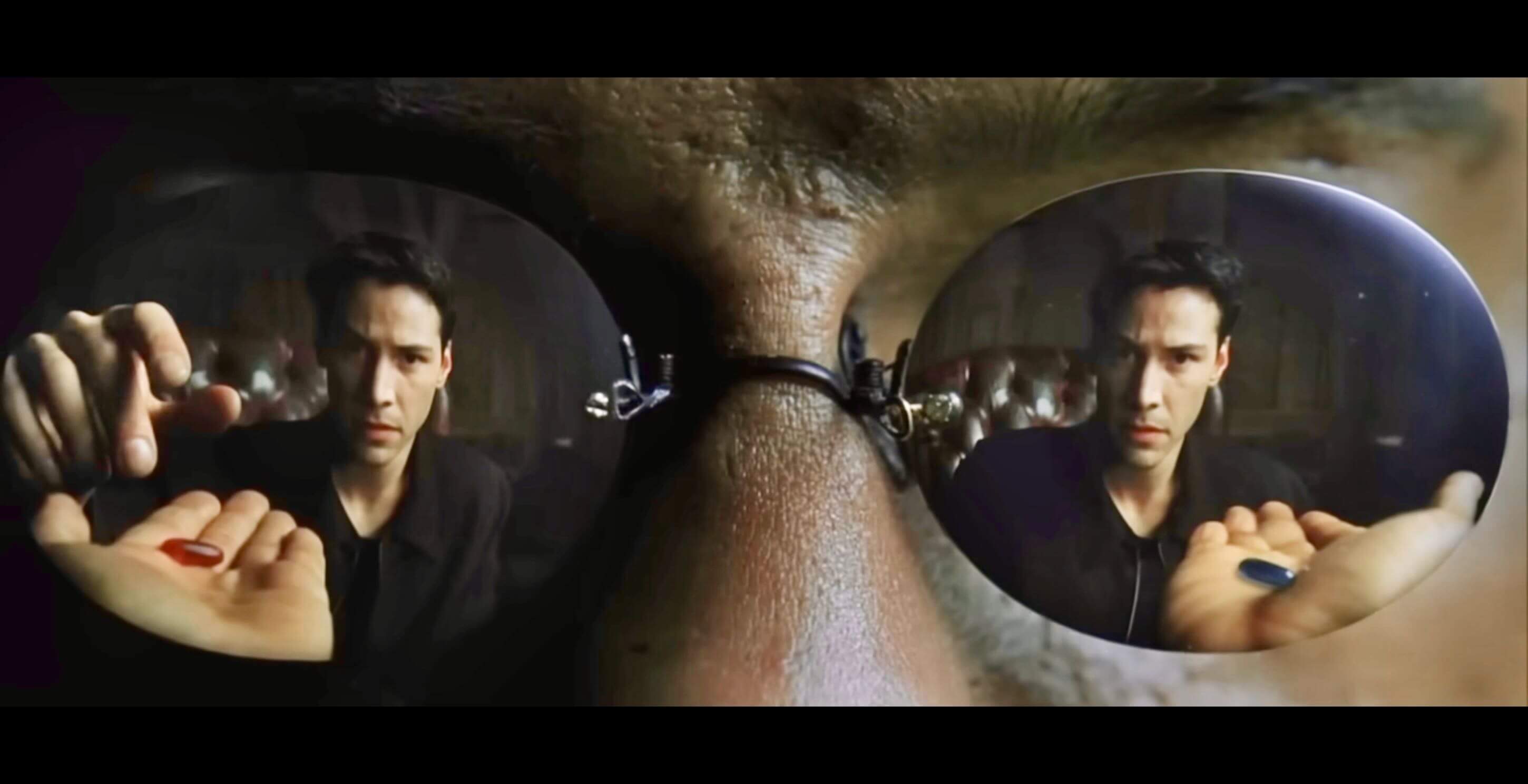

Chances are you can simply say "no" and keep your life exactly as it is. Or you can say "yes" and allow on-call to start changing you in ways you probably didn't anticipate.

Maybe you've already gone through this journey yourself. Or maybe you'll have to answer this exact question tomorrow. If so, I can't tell you what you should say, but I can tell you, in this article, how saying "yes" changed my life.

The good

To give some context, I joined an on-call rotation for a production service for the first time about nine years ago, none of my previous roles had involved being on-call. For most of that time I was on-call for a critical front-facing production service, the kind of service that shouldn't ever go down. And yet, every so often it would.

As an additional complication, I live in Australia, and the rest of the world is wide awake when we are asleep. So it's quite common for the peak traffic, which is a frequent trigger for incidents, to happen when it's the middle of the night here – waking the on-call engineer up. It's worth noting that this is less of an issue for giant companies that have engineering offices across all major timezones, but very few startups and smaller companies can afford this luxury.

You learn to deal with stress

When you receive an alert at 2am, you have to wake up, understand what's going on, fix the problem and provide updates, and all of this happening in the middle of the night can be incredibly stressful. This "on-call dance" is often hard to get used to because the causes are rarely the same, and yet after you go through this drill a few times, you learn to deal with it. This isn't simply because you got used to the process, you learn to deal with emergencies in general.

I've noticed this in myself – it's much easier to stay calm and act with a cool head in a real-life emergency situation when you've been through many incidents while on call before. Even though sitting in bed with a laptop at 2am and dealing with a severe injury in the middle of the forest look completely different, in both situations you're dealing with high amounts of stress.

You learn leadership and coordination skills

Not every incident occurs at 2am however, but it's not uncommon that when the whole system goes down, it turns into an all-hands-on-deck situation. Someone needs to start the mitigation using feature flags, someone might need to investigate the initial trigger, someone needs to provide a summary. As you deal with more and more incidents, at some point you'll find yourself leading the response, and these are important leadership and coordination skills that could be quite hard to acquire in other situations.

You learn systems in incredible depth

The incident response doesn't end after an hour of firefighting, it's followed by tens of hours of digging into what happened, and then making sure that it doesn't happen again. During those long debugging sessions, as you dissect the system and try to reconstruct the exact sequence of events, you learn the systems you work on at a much more intimate level than you ever would by just shipping changes.

You develop an appreciation for how systems interact, for CPU and memory constraints, for the intricacies of the runtime, all of which surface later as you design the future versions of those systems. You know what can go wrong, because you've seen those failure modes multiple times. Writing those detailed internal post-incident reports is what tuned my engineering thinking the most. Not to mention, many of those firefighting experiences become great stories to share.

The bad & the ugly

It's not all great and rosy, though.

You acquire physical constraints

When you're on-call, your life is inherently constrained by the need to always have your laptop with you and to stay within the bounds of reliable reception. How limiting this could feel depends on your lifestyle – if you spend your weekends tinkering with robots in your garage, that's not much of a problem, but if you're hiking in the mountains every weekend, being on-call quickly becomes a real burden.

The potential health effects

You're woken up at 1am, you start firefighting, the adrenaline is high, you mitigate the issue and go back to bed at 2am, and yet you struggle to fall asleep. Your mind is still racing, and only 30 minutes to an hour later do you finally fall back asleep. The next day you feel exhausted, your mind is foggy and you can't think straight. This is a situation that's unfortunately familiar to many on-call engineers, and depending on how often it's repeated, it can have adverse effects on your health. There have been multiple research papers highlighting the negative impact of sleep disruption and on-call work specifically, and it can even affect the quality of relationships.

This is the part that is easy to normalise but you shouldn't. Don't let yourself become so used to nightly alerts that you treat them as normal background noise. Find a way to fix the situation or find a way out. Every benefit listed above isn't worth much if the long-term price is your health, and being on call is only worth it if you can minimise the impact on your health.

Conclusion

I'm a firm believer in the "you build it, you run it" model, and I'm on-call as I'm writing this article. Luckily for me, the forecast for the weekend isn't great, so I'm not exactly missing out on a perfect day in the mountains.

If you're deciding whether to join an on-call rotation, I'd suggest giving it a try. It's not a one-way door, you can always reverse your decision. No judgement if you decide to say "no" either. I hope my experience helps you make that call. And if you're someone with years of on-call behind you, please do share your experience as well, and I'm sure you've collected plenty of great firefighting stories to share.

Discuss on

Subscribe

I'll be sending an email every time I publish a new post.

Or, subscribe with RSS.