By Sergey Tselovalnikov on 07 January 2025

Six Sins of Platform Teams

Platform teams are very common these days, and the approach has been widely adopted. When implemented successfully, platform teams become huge force multipliers, delivering a tremendous amount of value. But as with any engineering approach, there are common anti-patterns, let’s call them "sins", that can limit their potential. As someone who's been in various platform engineering roles and has committed many of these sins myself, I’ve built a certain mental model of the common sins that platform teams might commit and formed some opinions on how the sins can be avoided. And in this article, I’ll share this mental model with you.

I’ll go through the sins in their natural order and, for each one, I’ll suggest a possible solution. Note that I won’t be focusing on the surface issues that have largely been discussed already, e.g. excessive toil. Instead, I’ll focus on more subtle sins – the ones that don't immediately manifest themselves but that you can see if you know what to look for.

Most conspiracies are just capitalism.

What are platform teams?

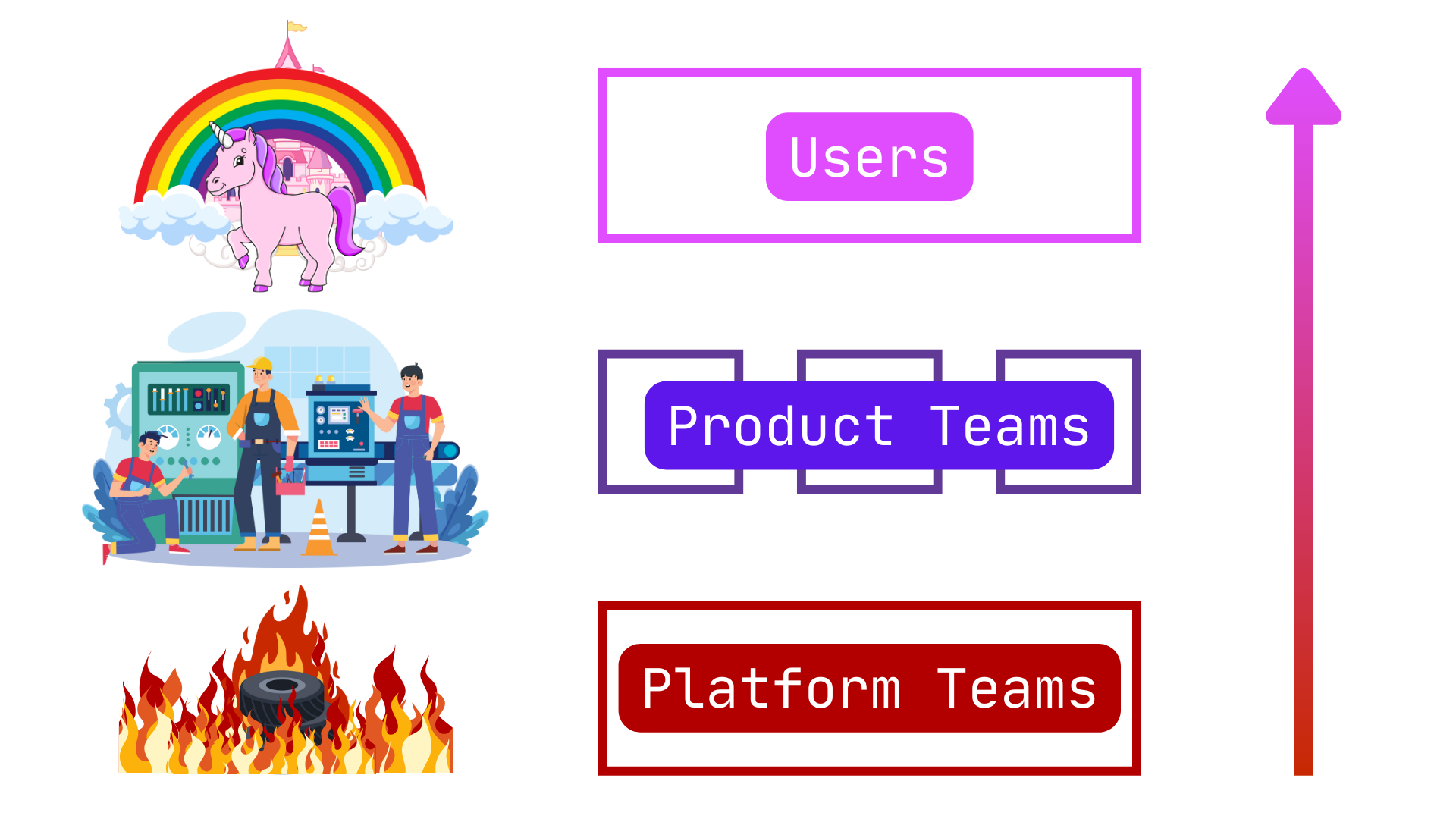

Before going further, let’s disambiguate the terminology, as platform teams is a very overloaded term. Within the scope of this article, platform teams are a way to implement the DevOps methodology at scale. The product teams are ultimately responsible for the complete lifecycle of the software they build, while being supported by platform teams. Even though there’s still a role separation, like in the pre-DevOps dev-and-sysadmin world, both platform and product teams take a software-first approach. Platform teams abstract the cross-cutting concerns into reusable platform components, helping product teams move faster while preserving their end-to-end ownership.

That said, this model only yields real benefits at a certain scale. The engineering organisation needs to be large enough for the de-duplication and unification benefits to outweigh the overhead of an added layer of indirection. Notably, as the company size grows, the volume of "platform" work that multiple teams would otherwise have to replicate also increases making platform teams more and more beneficial.

The Six Sins

Structuring the team around a particular solution to a problem

A while back, I watched a presentation by an engineer from Dropbox who told a great story about designing their new on-premise storage system called MagicPocket. He explained how it was tempting to call the team responsible for it the "MagicPocket Team" rather than the "Storage Team." But that would have been a crucial mistake. After all, this team’s ultimate responsibility was storage. If, one day, a cheaper cloud-based alternative emerged, they shouldn’t be tied to their MagicPocket solution, and instead they should choose the best solution for the "storage" problem.

That story really stuck with me, especially since I’ve also once been part of a team named after a specific microservice rather than the broader area it was meant to serve.

Solution

As compelling as it is to name teams after the tools they use – Envoy Team, Kubernetes Team, AWS/Azure/GCP Team, or Galactus Team – it’s better to name them after the problem they solve or the capability they provide instead. Focus on the mission and the problem the team is solving, not the implementation details of a particular solution.

Losing empathy towards product engineers

Platform engineers tend to work in deeply technical domains, often tightly scoped to a particular stage of the software development lifecycle. Since cross-team communication is often expensive, platform teams are often structured so each one clearly focuses on a specific area only. This naturally leads to teams setting clear boundaries around "their" part of the lifecycle, and communicating with each other through (well-)defined APIs.

Depending on how strict those boundaries are, the way platform teams build solutions might diverge significantly from how product engineers build things. A separate programming stack, CI/CD practices, etc. Eventually, every divergence in the day-to-day life of a product engineer from a platform engineers will add up to having less and less empathy platform engineers feel towards product engineers because they won't feel the same pains product engineers feel day to day.

In this environment, it’s very easy for platform teams to start living in its own ecosystem where achievements, while they can be technically impressive, do not necessarily result in improving the lives of real users, or in addressing the pains of product engineers.

Solution

The only real way forward is through communication and unification.

Communication: If you build software for cooks then the only way to learn what they need is to be in the kitchen for as much as you can, ideally cooking food yourself. Standard practices like dogfooding and rotating team members between product and platform roles help ensure that everyone knows the real pains the engineers face.

Unification: Use the same dev stack wherever possible. Each platform team should support not only the product teams but also the other platform teams. Using the same tools, the same language, the same libraries, the same everything means you’ll share the same pains as the product teams – if you’re feeling the pain, you’ll be far more motivated to solve it.

Short or Long term only focus

Now that the empathy is restored, there are two failure modes for any platform team. The first would be to address a plethora of paper cuts without a cohesive direction. This could often be a symptom of not having a deep understanding of the system as quite often the same root cause issue would manifest on the surface at random points. While in itself, this is often incredibly valuable, at some point, once all quick wins are harvested, each paper cut fix would take more and more time, while often bringing less and less value.

The second failure mode is the opposite, and it would typically manifest itself as trying to build the amazing and perfect solution that would be built from scratch to fix all existing problems. If taken long enough, by the time the solution is released, which is a big "if" already, it’ll likely be landing in a very different world to the one in which it was designed, and as a result, addressing a lot fewer problems, if any, than it was originally designed to fix.

Solution

The solution to this problem has two steps and it’s largely related to being able to analyse the system from the first principles. Doing so will allow you to first – uncover the root cause of the common issues even when they’re seemingly unrelated. And secondly, allow for a clear understanding of how the solution can be integrated into the existing state of the world bringing value iteratively as opposed to a big-bang solution that you have to wait many years for.

This path is not the simplest and is often not the first choice of many engineers as it requires diving deeply into the existing system, understanding the reasons behind the decisions that led to the current state, and in a way embracing the current world instead of starting from scratch and building a new and perfect one. Yet, making the revolution an evolution is the only path that would bring validation to the approach early and guarantee a smooth path.

Focusing on making things easy instead of making things simple

I hope that you have watched Simple Made Easy by Rich Hickey, and if you haven’t, I highly recommend watching at least the first ten minutes. In this talk, Rich Hickey highlights a big difference between something being easy to do and something being simple.

You’ve probably heard the classic pitch before: "Working with Foo is so hard. We’re going to make it easy to work with." Yet you rarely hear, "Foo is complex. We’re going to make it simple," despite the latter being a lot more valuable in the long run.

An easy to work with yet complex system can function well when everything works as expected and no changes to the system need to be made, which is rarely the case. And the larger the difference between the abstractions, the more likely that instead of investigating and possibly immediately spotting issues themselves, the product teams will have to reach out for support – often resulting in ping-pong communication possibly between many teams, which the whole DevOps methodology was aiming to eliminate – where product engineers do not have clear visibility into the abstraction underneath them, and the platform team does not have a clear understanding of the layer above that depends on them.

A single human brain can only hold so much. And once the threshold is crossed, and not a single person understands how a system works, the system becomes effectively "ossified" and large-scale changes become impossibly hard – not due to the number of changes or lines of code that need to be modified, but rather because no one can hold the full picture of how the system with many intertwined dependencies works.

Solution

A good start would be to rigorously trace whatever you do through a layer of abstractions, inspect each layer, the dependencies of this layer, and evaluate whether it actually adds any value. Each abstraction, each API layer on top of another API, and each dependency should be able to defend its right to stay.

You will probably still end up with a decent layer of abstractions and dependencies. After all, how else would a platform team be able to introduce cross-cutting changes? Now, try to make sure that each one deviates as little as possible from the layer above and the layer below. Don’t reach for a proxy built in another language or a new format in places where a tiny wrapper library with simple code would suffice. The more unified the stack is, the more often a simple method call can be made as opposed to an easy-to-do but hard-to-understand network call.

Treating product engineers as customers

This is a point I first encountered in the There’s No Such Thing As Internal Customers talk, and it resonated deeply with me. The talk argues that the notion of "internal customers" is fundamentally flawed which mirrors my experience.

Customers, by definition, have a choice. If customers use your product, it’s because they decided it provided value over alternatives, which is not the case with product teams most of the time. When product teams use your tools or platform, it’s not necessarily because they love it – it’s because they might have no other choice.

Then again, sometimes your actual customers – the ones who pay you money – will benefit from changes that make product engineers lives harder. And that’s okay. The platform team’s job isn’t always to make lives of product engineers easier, it’s to deliver value to real customers. It can indeed be done through improving the lives of product engineers, but never at the expense of the actual customer experience.

Solution

Always prioritise the actual customer – if a change makes life harder for product engineers but improves the customer experience, it’s often worth it. Treat product engineers as partners, not customers, and collaborate with them to align on solutions without designing solely for their convenience. When introducing changes, be transparent about how they benefit the end customer, always focus on the why part. Understanding the reasoning behind the changes will ensure that product engineers support them.

Building to expand your domain instead of working on the most impactful thing

It's easy for a platform engineer scoped on a particular domain to acquire tunnel vision where the domain they’re working on becomes the centre of their universe. Then, the team's roadmaps are always structured around the domain the team works on, and the work is prioritised relative to other tasks within the same domain, rarely against the tasks in the neighbouring domains.

Solution

As a platform engineer, eliminating the need for your current role within your domain shouldn’t be your fear. If you’ve built amazing tooling which users love, and something that used to be a huge pain is now a breeze then you’ve achieved your goal, even if there are still thousands of improvements that could be made.

Sometimes you need to pause and reflect. What would happen if you or your team simply did nothing for the next month, six months, or even a year? You might say, "Then we wouldn't ship Foo". But can you prove that shipping Foo results in improving lives of the actual customers? Maybe grab a few product engineers and ask them how they’d feel if Foo never saw the light of day. If they scream, "We needed Foo yesterday!" then great. But if all you get are shrugs and a "Wait, what’s Foo?" you might need to reconsider whether you’re working on the most impactful thing.

And remember, every project you take on costs more than just your effort, it comes with an opportunity cost – the things you’re not working on instead, possibly something that would truly matter. Maybe it’s time to let go of the grandiose plans for the platform you’ve already built and find something that would have a far greater impact. If you’re not sure what this could be, roll up your sleeves and join a product team deeply in the trenches. Ship a few user-facing features and believe me, you’ll quickly discover what actually hurts, and what truly needs fixing.

Conclusion

This article is by no means intended to criticise the concept of platform teams. On the contrary, I wholeheartedly believe they’re a great way to implement DevOps for companies of a certain size. Instead, my goal here is to highlight a few anti-patterns that can limit their impact and, in some cases, damage the overall reputation of this approach.

This article is based on my own mental model, and no model perfectly reflects reality. You can always find exceptions to any rule. It’s also likely incomplete – the list of "sins" I’ve described is by no means exhaustive. This article is also full of opinions, and it's quite likely you might disagree with some of those points. If you think I’ve missed something, or you simply disagree with any of the points, please share your thoughts. I'd be keen to have a discussion and update my mental model.

Discuss on

Subscribe

I'll be sending an email every time I publish a new post.

Or, subscribe with RSS.